- Home

- Philipp Meyer

The Son

The Son Read online

Dedication

For my family

Epigraph

In the second century of the Christian era, the Empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind . . .

. . . its genius was humbled in the dust; and armies of unknown Barbarians, issuing from the frozen regions of the North, had established their victorious reign over the fairest provinces of Europe and Africa.

. . . the vicissitudes of fortune, which spares neither man nor the proudest of his works . . . buries empires and cities in a common grave.

—EDWARD GIBBON

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my publisher, Dan Halpern, a fellow artist who gets it. Also Suzanne Baboneau. My agents, Eric Simonoff and Peter Straus. Libby Edelson and Lee Boudreaux.

I am grateful to the following organizations for their generous support: the Dobie Paisano Fellowship Program, Guggenheim Foundation, Ucross Foundation, Lannan Foundation, and the Noah and Alexis Foundation.

While any and all errors are the fault of the author, the following people were invaluable for their knowledge: Don Graham, Michael Adams, Tracy Yett, Jim Magnuson, Tyson Midkiff, Tom and Karen Reynolds (and Debbie Dewees), Raymond Plank, Roger Plank, Patricia Dean Boswell McCall, Mary Ralph Lowe, Richard Butler, Kinley Coyan, “Diego” McGreevy and Lee Shipman, Wes Phillips, Sarah and Hugh Fitzsimons, Tink Pinkard, Bill Marple, Heather and Martin Kohout, Tom and Marsha Caven, Andy Wilkinson, everyone at the James A. Michener Center for Writers, André Bernard, for his sympathetic ear, Ralph Grossman, Kyle Defoor, Alexandra Seifert, Jay Seifert, Whitney Seifert, and Melinda Seifert. Additionally, I am grateful to Jimmy Arterberry of the Comanche Nation Historic Preservation Office, Juanita Pahdopony and Gene Pekah of Comanche Nation College, Willie Pekah, Harry Mithlo, and the Comanche Language and Cultural Preservation Committee, though this in no way implies their endorsement of this material. It is estimated that the Comanche people suffered a 98 percent population loss during the middle period of the nineteenth century.

RIP Dan McCall.

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgments

Family Tree

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Chapter Fifty-five

Chapter Fifty-six

Chapter Fifty-seven

Chapter Fifty-eight

Chapter Fifty-nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-one

Chapter Sixty-two

Chapter Sixty-three

Chapter Sixty-four

Chapter Sixty-five

Chapter Sixty-six

Chapter Sixty-seven

Chapter Sixty-eight

Chapter Sixty-nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-one

Chapter Seventy-two

About the Author

Also by Philipp Meyer

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Colonel Eli McCullough

Taken from a 1936 WPA Recording

It was prophesied I would live to see one hundred and having achieved that age I see no reason to doubt it. I am not dying a Christian though my scalp is intact and if there is an eternal hunting ground, that is where I am headed. That or the river Styx. My opinion at this moment is my life has been far too short: the good I could do if given another year on my feet. Instead I am strapped to this bed, fouling myself like an infant.

Should the Creator see fit to give me strength I will make my way to the waters that run through the pasture. The Nueces River at its eastern bend. I have always preferred the Devil’s. In my dreams I have reached it three times and it is known that Alexander the Great, on his last night of mortal life, crawled from his palace and tried to slip into the Euphrates, knowing that if his body disappeared, his people would assume he had ascended to heaven as a god. His wife stopped him at the water’s edge. She dragged him home to die mortal. And people ask why I did not remarry.

Should my son appear, I would prefer not to suffer his smile of victory. Seed of my destruction. I know what he did and I suspect he has long graced the banks of the river Jordan, as Quanah Parker, last chief of the Comanches, gave the boy scant chance to reach fifty. In return for this information I gave to Quanah and his warriors a young bull buffalo, a prime animal to be slain the old way with lances, on my pastures that had once been their hunting grounds. One of Quanah’s companions was a venerable Arapahoe chief and as we sat partaking of the bull’s warm liver in the ancient manner, dipped in the animal’s own bile, he gave me a silver band he had personally removed from the finger of George Armstrong Custer. The ring is marked “7th Cav.” It bears a deep scar from a lance, and, having no suitable heir, I will take it to the river with me.

Most will be familiar with the date of my birth. The Declaration of Independence that bore the Republic of Texas out of Mexican tyranny was ratified March 2, 1836, in a humble shack at the edge of the Brazos. Half the signatories were malarial; the other half had come to Texas to escape a hangman’s noose. I was the first male child of this new republic.

The Spanish had been in Texas hundreds of years but nothing had come of it. Since Columbus they had been conquering all the natives that stood in their way and while I have never met an Aztec, they must have been a pack of mincing choirboys. The Lipan Apaches stopped the old conquistadores in their tracks. Then came the Comanche. The earth had seen nothing like them since the Mongols; they drove the Apaches into the sea, destroyed the Spanish Army, turned Mexico into a slave market. I once saw Comanches herding villagers along the Pecos, hundreds at a time, no different from the way you’d drive cattle.

Having been trounced by the aboriginals, the Mexican government devised a desperate plan to settle Texas. Any man, of any nation, willing to move west of the Sabine River would receive four thousand acres of free land. The fine print was written in blood. The Comanche philosophy toward outsiders was nearly papal in its thoroughness: torture and kill the men, rape and kill the

women, take the children for slaves or adoption. Few from the ancient countries of Europe took the Mexicans up on their offer. In fact, no one came at all. Except the Americans. They flooded in. They had women and children to spare and to him that overcometh, I giveth to eat of the tree of life.

IN 1832 MY father arrived in Matagorda, common in those days if you viewed the risk of death by firing squad or a scalping by the Comanches as God’s way of telling you there were great rewards to be had. By then the Mexican government, nervous about the growing Anglo horde within its borders, had banned American immigration into Texas.

And still it was better than the Old States, where unless you were son of a plantation owner, there was nothing to be had but the gleanings. Let the records show that the better classes, the Austins and Houstons, were all content to remain citizens of Mexico so long as they could keep their land. Their descendants have waged wars of propaganda to clear their names and have them declared Founders of Texas. In truth it was only the men like my father, who had nothing, who pushed Texas into war.

Like every able-bodied Scotsman, he did his part in the rout at San Jacinto and after the war worked as a blacksmith, gunsmith, and surveyor. He was tall and easy to talk to. He had a straight back and hard hands and people felt safe around him, which proved, for most of them, to be an illusion.

MY FATHER WAS not religious and I attribute my heathen ways to him. Still, he was the sort of man who felt the breath of the pale rider close on his neck. He did not believe in time to waste. We first lived at Bastrop, raising corn, sorghum, and hogs, clearing land until the new settlers came in, those who waited until the Indian dangers had passed, then arrived with their lawyers to challenge the deeds and titles of those who had civilized the country and vanquished the red man. These first Texans had purchased their holdings with the original human currency and most could neither read nor write. By the age of ten I had dug four graves. The faintest sound of galloping hooves would wake the entire family, and by the time the news arrived—some neighbor cut up like a Thanksgiving shoat—my father had checked his loads and then he and the messenger would disappear into the night. The brave die young: that is the Comanche saying, but it was true of the first Anglos as well.

During the ten years Texas stood alone as a nation, the government was desperate for settlers, especially those with money. And through some invisible telegraph the message went back to the Old States—this area is safe now. In 1844 the first stranger arrived at our gate: a barbershop shingle, store-bought clothes, a lady-broke sorrel. He asked for grain as his horse would founder on grass. A horse that could not eat grass—I had never heard of such a thing.

Two months later, the Smithwicks’ title was challenged and then the Hornsbys and MacLeods were bought out at a pittance. By then there were more lawyers in Texas, per capita, than any other place on the continent and within a few years all the original settlers had lost their land and been driven west again, back into Indian country. The gentler classes who had stolen the land were already plotting a war to protect their blacks; the South would be cursed but Texas, a child of the West, would emerge unscathed.

In the meantime a campaign was launched against my mother, a Castilian of the old line, dark skinned but finely featured, it was claimed by the new settlers that she was octoroon. The plantation gentleman took pride in his eye for such things.

By 1846 we had moved past the line of settlement, to my father’s headright on the Pedernales. It was Comanche hunting grounds. The trees had never heard an ax, and the land and all the animals who lived upon it were fat and slick. Grass up to the chest, the soil deep and black in the bottoms, and even the steepest hillsides overrun with wildflowers. It was not the dry rocky place it is today.

Wild Spanish cattle were easily acquired with a rope—within a year we had a hundred head. Hogs and mustang horses were also for the taking. There were deer, turkey, bear, squirrel, the occasional buffalo, turtles and fish from the river, ducks, plums and mustang grapes, bee trees and persimmons—the country was rich with life the way it is rotten with people today. The only problem was keeping your scalp attached.

Chapter Two

Jeanne Anne McCullough

March 3, 2012

There were murmurs and quiet voices, not enough light. She was in a large room that she first mistook for a church or courthouse and though she was awake, she couldn’t feel anything. It was like floating in a warm bath. There were dim chandeliers, logs smoking in a fireplace, Jacobean chairs and tables and busts of old Greeks. There was a rug that had been a gift from the Shah. She wondered who would find her.

It was a big white house in the Spanish style; nineteen bedrooms, a library, a great room and ballroom. She and her brothers had all been born here but now it was nothing more than a weekend house, a place for family reunions. The maids wouldn’t be back until morning. Her mind was perfectly awake but the rest of her seemed to have been left unplugged and she was fairly certain that someone else was responsible for her condition. She was eighty-six years old, but even if she liked telling others that she couldn’t wait to cross over to the Land of Mañana, it was not exactly true.

The most important thing is a man who does what I tell him. She had said that to a reporter from Time magazine and they’d put her on the cover, forty-one and still sultry, standing on her Cadillac in front of a field of pumpjacks. She was a small, slender woman, though people forgot this soon after meeting her. Her voice carried and her eyes were gray like an old pistol or blue norther; she was striking, though not exactly beautiful. Which the Yankee photographer must have noticed. He had her open her blouse another notch and did her hair like she’d stepped out of an open car. It was not the height of her power—that had come decades later—but it was an important moment. They had begun to take her seriously. Now the man who’d taken the photograph was dead. No one is going to find you, she thought.

Of course it was going to happen this way; even as a child she’d been mostly alone. Her family had owned the town. People made no sense to her. Men, with whom she had everything in common, did not want her around. Women, with whom she had nothing in common, smiled too much, laughed too loud, and mostly reminded her of small dogs, their lives lost in interior decorating and other peoples’ outfits. There had never been a place for a person like her.

SHE WAS YOUNG, eight or ten, sitting on the porch. It was a cool day in spring and the green hills went on as far as she could see, McCullough land, as far as she could see. But something was wrong: there was her Cadillac, parked in the grass, and the old stables, which her brother had not yet burned, were already gone. I am going to wake up now, she thought. But then the Colonel—her great-grandfather—was speaking. Her father was there as well. She’d once had a grandfather, Peter McCullough, but he had disappeared and no one had anything good to say about him and she knew she would not have liked him either.

“I was thinking you might make a showing at the church this Sunday,” her father said.

The Colonel thought those things were best left to the Negroes and Mexicans. He was a hundred years old and did not mind telling people they were wrong. His arms were like gunsticks and his face was splotchy as an old rawhide and they said the next time he fell, it would be right into his own grave.

“The thing about preachers,” he was saying, “is if they ain’t sparkin’ your daughters, or eatin’ all the fried chicken and pie in your icebox, they’re cheatin’ your sons on horses.”

Her father was twice the size of the Colonel, but, as the Colonel was always pointing out, he had a strong back and a weak mind. Her brother Clint had bought a horse and saddle off that pastor and there had been a setfast under the blanket nearly the size of a griddle cake.

HER FATHER MADE her go to church anyway, waking up early to make the trip to Carrizo, where they had a Sunday school. She was hungry and could barely keep her eyes open. When she asked the teacher what would happen to the Colonel, who was sitting home that very minute, likely drinking a julep, the

teacher said he was going to hell, where he would be tortured by Satan himself. In that case, I am going with him, Jeannie said. She was a disgraceful little scamp. She would have been whipped if she were Mexican.

On the ride home, she could not understand why her father sided with the teacher, who had a beak like an eagle and smelled like something inside her had died. The woman was ugly as a tar bucket. During the war, her father was saying, I promised God that if I survived, I would go to church every Sunday. But just before you were born, I stopped going because I was busy. And do you know what happened? She did—she had always known. But he reminded her anyway: Your mother died.

Jonas, her oldest brother, said something about not scaring her. Her father told Jonas to be quiet and Clint pinched her arm and whispered, When you go to hell, the first thing they do is shove a pitchfork up your ass.

She opened her eyes. Clint had been dead sixty years. Nothing in the dim room had moved. The papers, she thought. She had saved them from the fire once and had not gotten around to destroying them. Now they would be found.

Chapter Three

Diaries of Peter McCullough

AUGUST 10, 1915

My birthday. Today, without the help of any whiskey, I have reached the conclusion: I am no one. Looking back on my forty-five years I see nothing worthwhile—what I had mistaken for a soul appears more like a black abyss—I have allowed others to shape me as they pleased. To ask the Colonel I am the worst son he has ever had—he has always preferred Phineas and even poor Everett.

This journal will be the only true record of this family. In Austin they are planning a celebration for the Colonel’s eightieth birthday, and what will be honestly said about a man who is lionized in capitols, I don’t know. Meanwhile, our bloody summer continues. The telephone lines to Brownsville cannot be kept open—every time they are repaired, the insurgents blow them up. The King Ranch was attacked by forty sediciosos last night, there was a three-hour gun battle at Los Tulitos, and the president of the Cameron Law and Order League was shot to death, though whether the latter is a gain or loss, I can’t say.

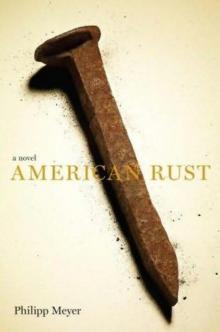

American Rust

American Rust